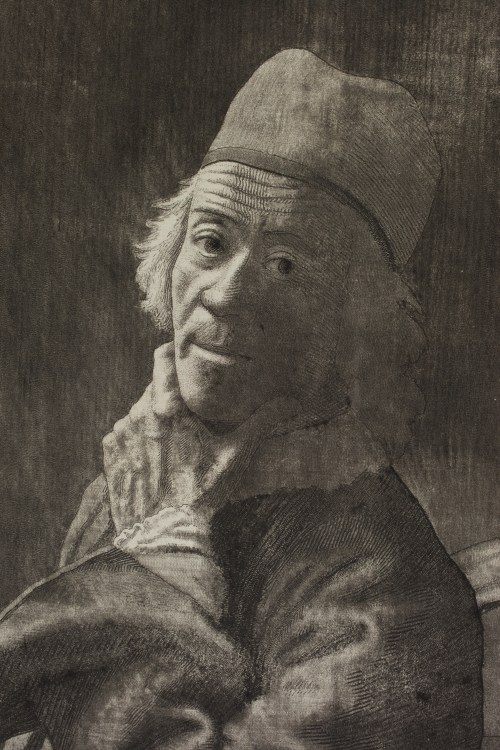

Jean-Étienne LIOTARD: Autoportrait, la main au menton (grande planche) [The Large Self-Portrait] - ca. 1778/1781

SOLD

Roulette and engraving over mezzotint, 466 x 394 mm (sheet). Humbert, Revilliod and Tilanus 8 (undescribed state), Rœthlisberger and Loche 522, 1st state (of 2).

Impression of the first state (of 2), before the letter in the lower margin of the copperplate. Very fine impression printed on laid paper, trimmed inside the platemark in the blank part by about 4 mm in width and 13 mm in height. In very good condition. An 18th century annotation in ink on the back of the sheet: n°15 and a more recent annotation in pencil: Portrait de J.E. Liotard / gravé par lui-même.

Provenance: Jean-Étienne Liotard, then by descent within the artist’s family.

Jean-Étienne Liotard produced very few prints: Marcel Rœthlisberger and Renée Loche listed fourteen original prints in 2008, as well as two prints on which Liotard only engraved the subjects’ faces; to this we should add the portrait of Archduchess Maria Anna of Austria, as reported by Perrin Stein in 2010 (« A Rediscovered Liotard », in Print Quarterly, March 2010, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 55-60). Impressions of these prints are all rare. The copperplates have not been preserved and there are no posthumous impressions known.

M. Roethlisberger and R. Loche quote 5 impressions of The Large Self-portrait in 2008: 2 impressions of the 1st state and 3 of the 2nd state. To date, we count 10 impressions: 5 impressions of the 1st state (Rijksmuseum d’Amsterdam acquired in 1908, British Museum acquired in 1931, Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired in 1949, an impression sold at Christie's on January 29 2019 and the present impression, coming from the painter's family); and 5 impressions of the 2nd state (Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva, Eidgenössiche Technische Hochschule in Zürich (quoted by Roethlisberger and Loche), National Gallery of Art de Washington acquired in 1953, The Art Institute of Chicago (acquisition number 53.272, quoted in Regency to Empire, p. 245) and an impression sold at Christie’s in 2009, then included in Nicolaas Teeuwisse’s Catalogue IX, no. 26, in 2010, and now at the Fondation Custodia in Paris).

The Autoportrait, la main au menton (grande planche) is considered to be Liotard’s printed masterpiece. It reuses the same composition as a pastel that was probably done in Geneva around 1770 and that Liotard exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1773 (R. and L. 447 ; Geneva, MAH, inv. 1925-5 ; 635 x 510 mm), for which there is a preparatory sketch in black stone and white chalk with sanguine highlights on blue-tinged paper, which Liotard exhibited in Paris in 1771 (R. and L. 447, preparatory sketch ; Geneva, MAH, inv. 1960-32 ; 488 x 359 mm). The engraving made in reverse after the pastel a few years later is noticeably different from both the pastel and the drawing: Liotard represented himself in more of a profile pose, and looks more directly at the viewer, with a slight, inquisitive smile. He also added behind him the top of the back of a chair called ‘bernoise’, that was produced at the time in Romandy, Switzerland: the moulded crosspiece is of a simple, unadorned style, contrary to the one in Autoportrait à la longue barbe from 1751-1752 (R. and L. 196 ; Geneva, MAH, inv. 1843-5). His hand is more clearly visible, emerging further from his sleeve than in the pastel and the sketch: the bones and sinews are apparent, etched in an energetic, nervous style. The sleeve of his kaftan folds back on itself, revealing the scalloped hem of his shirt sleeve, as is the case in other self-portraits. A few strands of hair stick out from under his cap on the side of his face that is in the light, in a similary way to Autoportrait riant which he painted around 1768 (R. and L. 446 ; Geneva, MAH, inv. 1893-9).

The Autoportrait, la main au menton (grande planche) belongs in a group of engravings that Liotard made between 1778/1781: the technique is close to the mezzotint and sets these engravings apart from five etchings made fifty years earlier. In addition to the portraits of Maria Anna of Austria and her sister Maria Christina of Austria (Duchess of Teschen), this group includes family portraits and portraits of important people, as well as subjects from Classical Antiquity and genre scenes, that Liotard used to illustrate his Traité des principes et des règles de la peinture (‘A Treatise on the Principles and Rules of Painting’) published in 1781. The plates unbound and bigger than the book were numbered I to VII for the reader’s reference. They could also be sold separately, as Liotard points out in his Avertissement (‘Foreword’).

In the second state of the Autoportrait, la main au menton (grande planche), Liotard engraved in the bottom margin: N°.1. I.E. LIOTARD. Gravé par lui-même // Effet. Clair obscur sans sacrifice. (‘Engraved by himself / Chiaroscuro effect, no sacrifice’) This letter clearly indicates that he was planning to use the plate in order to illustrate his Traité. However, he also engraved the same letter underneath a smaller and slightly modified version of the self-portrait (R. and L. 523, 200 x 160 mm approx.). Of the seven plates listed in the Avertissement to his Traité, Liotard describes N°. I. as a Portrait de l’auteur, with no mention of the size or any other element that would help us know which version he was referring to. Since both portraits bear the same letter, M. Rœthlisberger and R. Loche assumed that Liotard had planned to replace one with the other, without however being able to tell which one had been engraved first. In the second state of the ‘grande planche’ however, we can see that the letter N in ‘N°’ is a print capital letter followed by an Arabic numeral, whereas on the smaller plate, just like in the other six plates that illustrate the Traité, the N is a cursive capital letter, followed by a Roman numeral. We can then surmise that Liotard had wanted to use the larger Autoportrait, but then changed his mind and made a smaller version for the Traité. It seems that he used the copperplate for the smaller self-portrait in order to test a printer, as indicated in his letter dated 6 April 1781 to his Geneva friend François Tronchin: ‘I was told that there is here a good printer for engravings, I will feel him out and have him print my small portrait that I have here.’ (Rœthlisberger and Loche, vol. 2, p. 756, translated by us). Liotard was in Lyon at the time, staying with his nephews the Lavergne ; he took refuge there in March 1781 for political and safety reasons (M. Rœthlisberger and R. Loche, vol. 1, p. 47). Even though the title page of his Traité indicates Geneva as place of publishing, it is in Lyon that he had the manuscript proofread and edited, and that is where he then completed the writing and had the book printed in July 1781. The plate that he calls ‘my small portrait’ in his letter to Tronchin is beyond doubt the smaller version of the self-portrait. It is quite likely that he didn’t take any other plates with him to Lyon, since on 29 May he asked Tronchin to send him from Geneva a crate of engraved plates which was under his bed in his bedroom, in order to have them printed at the same time as his book. He does not list the contents of the crate, and so it is not possible to know whether the copperplate for the larger Autoportrait was in it.

Liotard’s Traité des principes et des règles de la peinture had no success. The preserved copies, as well as the plates, are very rare. In the foreword, Liotard lists the reasons why he thought it appropriate to give his self-portrait as an example: ‘It has seemed judicious to offer it up for consideration due to the chiaroscuro, the harmony between dark areas, and the just distance to be observed between light and dark parts.’ (Traité, p. 4, translated by us). Under the entry devoted to chiaroscuro, he explains further: ‘See N°. I. my portrait: I endavoured to give it a good chiaroscuro; and while the dark areas are strong, they are nonetheless soft, not having sacrificed light shades. The shadow of the hair and the shirt being slightly darker than the lightest light of the garment, the half-figure is well delineated against its background ; in this several principles have been applied, that I will try to further explain in this work.’ (p. 23, translated by us). One of these principles consists in achieving effect by ‘marrying saliency and chiaroscuro. That effect is the part which at first sight moves the viewer and strikes his eye, and better captures the mind of spectators. The best and simplest means to produce such an effect is to choose and to apportion half dark and half light shades, and most importantly to put an equal distance between light and dark, such as is seen in nature. See my portrait N°. I.’ (p. 25, translated by us). Liotard again refers the reader to his portrait in order to illustrate the notion of saliency, or the art of making painted objects appear three-dimensional, and gives the portrait as an example for rule III: ‘Never should a dark shade look like a light one, and the lightest light shade should still be lighter than the lightest dark one’: ‘See N°. I., my portrait, the white hair and the shirt in the shadows are slightly darker than the lowest light of the habit.’ (p. 32, translated by us). Again the self-portrait serves to illustrate one of the principles dearest to Liotard: that ‘touches’ should be avoided at all costs, since ‘one cannot see such ‘touches’ in the works of nature’ and ‘one should never paint what one does not see (pp. 39-40, translated by us). To touches Liotard prefers finish, which ensures a perfect connection between the different parts of the work, and makes it possible to reproduce ‘the unified tint of a beautiful skin, the smoothness and the transparency of bodies, the colour of flowers, the fluff, the velvety to be seen on fruit […]’. Rule IX summarises the proper distribution of lights and darks that will produce effect and saliency. Interestingly, here Liotard refers the reader to the three versions of his self-portrait: the pastel that was exhibited and sold in London in 1773, the preparatory sketch, which, he informs viewers, can be seen at his house, and the engraved portrait. He explains that through these three techniques he endeavours to apply the same principles, guided by the same exacting search for truth in rendering nature, and the same concern for details and finish: ‘The most disciplined reasoning, concentration and thought are required in order to be able to imitate, on a flat surface, the roundness and relief of nature.’ (p. 59, translated by us).

When Liotard took up engraving again, fifty years after his only five etchings, he settled on the technique of mezzotint. He probably had the opportunity to see mezzotints during his two trips to London in 1753-1755 and 1773-1774, since the technique was then enjoying a vogue in England. Victor I. Carlson wonders whether Liotard was able to see the famous series of large portraits engraved in mezzotint by Thomas Frye in the 1760s. Anyway, Liotard adapted mezzotint to suit his own aesthetic research, by experimenting and combining different techniques for intaglio printmaking. The result was a brilliant success: Campbell Dodgson declared it ‘a performance so novel and imposing’ when the British Museum acquired an impression of the first state of Autoportrait, la main au menton (The British Museum Print Quarterly, 1931, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 4), and it is ‘a tour de force of roulette and engraving over mezzotint’, according to Victor I. Carlson (Regency to Empire, cat. 84, p. 245). To begin with, Liotard prepared the whole background of the plate with a rocker and a roulette; he then burnished the surface in order to highlight light areas, which corresponds to the traditional technique of mezzotint. However, according to Carol Wax, ‘the most interesting aspect of the image is the textures that were added with very small rockers of different gauges’ (C. Wax, The Mezzotint. History and Technique, p. 88). The use of different sizes of rockers and roulettes allowed Liotard to reproduce not only the different textures of skin, hair and the vaporous fabric of the shirt or the heavier fabric of the kaftan, but also the differences in light, from lighter to darker shades, without sacrificing one to the other.

Even if the smaller version of the Autoportrait might seem at first sight almost identical, Liotard used a much simpler technique. Roethlisberger and Loche remark that ‘contrary to the large plates, the whole surface is made up of a very fine grid pattern which remains clearly visible and gives the image a unity of style that verges on the abstract’ (R. and L. cat 523). This simplification means that the small self-portrait loses a good part of the spirited energy that was evident in the large plate, which put it on a par with the self-portraits that Liotard painted or drew. Liotard’s self-portraits, created at different times in his life, represent an artist who is exacting in his art, a nonconformist who variously dresses up as a Turk with a long beard or smiles to reveal a toothless grin.

The self-portrait of the older Liotard has been compared to some self-portraits by contemporary artists. Martin Hopkinson remarks that “In its honesty and poignancy, this image rivals the late self-portraits of Chardin” (« Liotard », in Print Quarterly, Notes, September 2004, vol. 21, no. 3, p. 298).

References: Marcel Roethlisberger and Renée Loche, Liotard, Catalogue, Sources et correspondance, 2008; Martin Hopkinson « Liotard », in Print Quarterly, Notes, September 2004, vol. 21, no. 3, p. 298; Campbell Dodgson, « Liotard's Portrait of Himself », in The British Museum Print Quarterly, 1931, vol 6, no. 1; Regency to empire: French printmaking, 1715-1814, 1984; « A Rediscovered Liotard », in Print Quarterly, March 2010, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 55-60; Humbert, Revilliod and Tilanus, La vie et les œuvres de Jean Étienne Liotard, 1702-1789, 1897; Carol Wax, The mezzotint: history and technique, 1990.