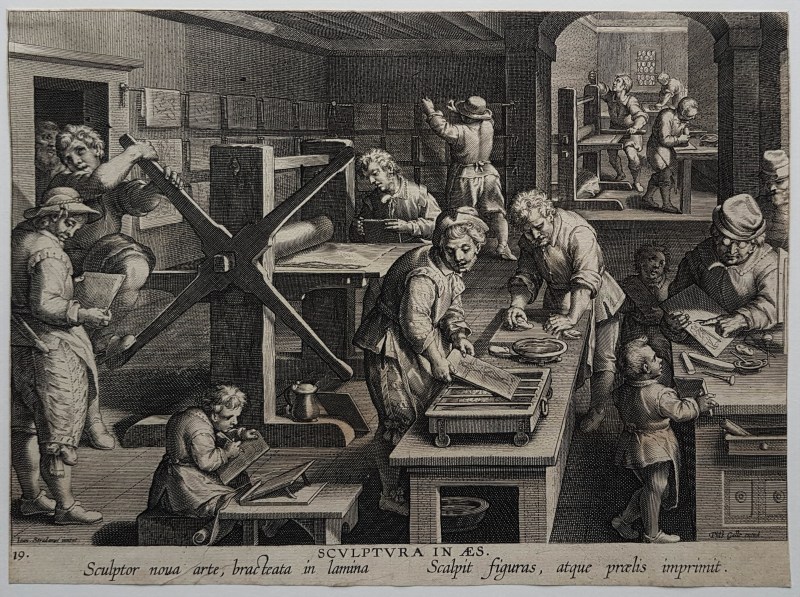

D’après Johannes STRADANUS : Sculptura in æs - c. 1591

SOLD

[The Invention of Copper Engraving]

Engraving, 202 x 273 mm. New Hollstein (Johannes Stradanus) 341 2nd state (of 4).

Impression of the 2nd state (of 4), with the number 19 added in margin at left, with Philips Galle’s address, before Johannes Galle’s address.

Very fine impression printed on laid watermarked paper (indistinct composition in a circle). Impression trimmed 1 mm outside the borderline or on the borderline, the text caption well preserved. A pale stain in the center of the composition, mainly visible verso, and two very short printer creases bottom left. Otherwise in very good condition.

Sculptura in æs is the last plate, bearing number 19, in a series of twenty engravings; the first plate in the series, which isn’t numbered, has the title Nova Reperta. This series was engraved by several artists after Johannes Stradanus; not all of them have been identified. Some plates are signed by Theodoor Galle (plate number 1) and Jan II Collaert (plates 15, 17 and 18). Four other plates have also been attributed to the latter: the plates with numbers 2, 12 and 16, as well as the title plate (see New Hollstein, The Collaert Dynasty, nos. 1205-1211). The series was first published around 1591 by Philippe Galle in Antwerp and was then successively republished by Karel de Mallery (after 1612), Theodoor Galle (before 1636) and Johannes Galle (before 1677).

The Nova Reperta series illustrates several noteworthy discoveries and inventions in late 16th century Europe: ranging from the exploration of the Americas to the cultivation of sugarcane, including the invention of the compass or the development of gunpowder.

Impressio librorum and Sculptura in æs represent a typographical printer’s shop for the former, and a workshop for intaglio printmaking for the latter. Several drawings by Johannes Stradanus are in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, among which the preparatory drawing for Impressio librorum: the resulting engraving is faithful to its detail. In the same collection is another drawing by the Flemish master, representing an engravers’ workshop in a format similar to Sculptura in æs. This drawing however, even though it is often mentioned as a preparatory drawing for the engraving, clearly differs from the print in the series. Its composition is not only different but Stradanus drew two screw-presses for printing books and woodcuts, while the engraving in Nova Reperta shows two roller-presses, or intaglio presses, used printing copperplates: “Intaglio printmaking requires the use of a specific printing press, which consists in a table held in place by wooden pillars, with a moving board placed between two wooden cylinders; the printer controls its movement with a handwheel.” (Maxime Préaud, Techniques de la gravure, online article, our translation). Stradanus’ drawing does indeed show engravers in æs, that is to say, on copper, and not engravers on wood: showing screw presses is thus a mistake, because such presses cannot exert the required pressure for intaglio printmaking. The mistake has been corrected in the engraving, perhaps on the basis of another preparatory drawing, now lost. On the left in the print, a man is working the huge roller press: his effort is depicted in a very realistic way, his foot pressing down on one of the arms of the press, and he is looking up to the ceiling. The freshly printed engravings are hung to dry on lines at the back of the room.

While the drawing focuses on the work of engraving copperplates, Sculptura in æs foregrounds the careful inking of the copperplate: successful printing depends on this step. “The plate must be inked all over with an ink that is greasy and soft but not liquid; the printer works the ink into the strokes with a pad (or poupée) while the plate is set on a burner, as the heat will soften the ink. Then the printer wipes off all the ink from the surface of the plate, first with rags, then with the palm of their hand, leaving only the ink in the hollows and strokes.” (M. Préaud, our translation). We can see two workers taking care of these two successive tasks in the centre of the print: one is holding a plate over a brazier, while the other is wiping off the ink from a plate laid flat on the workbench. In a recess at the back, others are busy working with a second press.

The engraving work itself in fact takes up little space in this print. In Stradanus’ drawing, the engravers were in the centre of the composition (five of them were gathered around the table, busy engraving and drawing); in the final print, there is only one engraver, to the right of the composition, teaching his craft to two very young apprentices. On the table, the tools of his trade are laid out: engraving tools, whetstones, rag.

Sculptura in æs puts the emphasis less on the invention of copperplate engraving, and more on the invention of the roller press, which allowed intaglio to soar as an art. Ad Stijnman, who undertook an exhaustive study of the history of the development of manual intaglio printmaking processes in his book Engraving and Etching 1400-2000, notes that, when copperplate engraving appeared in Europe around 1430, it wasn’t done with a press but by hand, by rubbing the back of the paper laid against the copperplate. This would result in very weak impressions of unequal quality. The use of roller presses was probably inspired by textile printing presses and started around 1460-1465. According to Jacques Bocquentin, as quoted by Ad Stijnman, the first roller press appeared in 1460-1465 in the Upper Rhine region, possibly in the workshop of the Master E.S. (Stijnman p. 39). The first known depiction of an engraver’s workshop is a small woodcut, attributed to Arnold Nicolai, that was introduced in the 2nd edition of Emblemata, et aliquot nummi antiqui operis by Johannes Sambucus, published by Plantin in 1564 in Antwerp. The scene is rather simplistic and features only one character. Sculptura in æs is the first detailed and realistic depiction of an engraving workshop, where the division of tasks evokes the level of sophistication of the process as well as the distribution of a high number of impressions.

Reference: Ad Stijnman: Engraving and Etching 1400-2000, A History of the Development of Manual Intaglio Printmaking Processes, 2012.