Jean-Etienne LIOTARD: Self-Portrait as a Young Man - ca. 1731

SOLD

Etching, 117 x 100 mm. Tilanus 1; Roethlisberger and Loche 18.

Counterproof (1), printed on laid paper, of the 1st state (of 3) of which no impression is known ; before new strokes in the hair, on the face and in the background. Sheet: 123 x 107 mm. Mounted à claire-voie (openwork) on a laid paper sheet (240 x 165 mm).

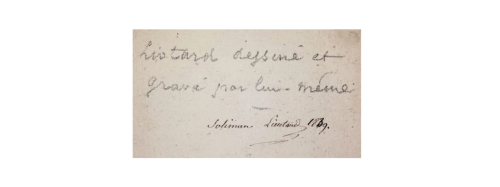

Old annotation in pencil on the back: Liotard dessiné et gravé par lui-même [Liotard sketched and etched by himself]; below, written in ink collection mark: Soliman Lieutaud 1839 (Lugt 1682).

Provenance: Soliman Lieutaud; Hippolyte Destailleur.

While Liotard painted or sketched twenty self-portraits, in oils, in pastel, in chalk or in enamel, he only ever etched two: the first one around 1731, the second one fifty years later, around 1780. He was around thirty when he etched this very unusual (Leeflang, 2011) self-portrait, in three-quarters view and in close-up; his unruly locks of hair remind us of Rembrandt's disheveled self-portraits when he was about the same age. The date of the work remains uncertain: 1730 (Leeflang, Rijksmuseum); 1731 (R.M. Hoisington); 1732 (this date written in ink on the impression in the Album Louis-Philippe - Château de Versailles et de Trianon); 1733 (British Museum, The Metropolitan Museum). The impression of the third state currently in the collection of the Bibliothèque nationale de France has an annotation that had previously been mistakenly attributed to Liotard (Tilanus, 1897) and which gives the date of 1733. On the etching, Liotard seems slightly older than in the 1727 self-portrait in oils, which Tilanus thought was a very good likeness (Tilanus, 1897, p. 140). According to Roethlisberger and Loche, there is no convincing clue which would allow us to date this etching with certainty.

Etching a self-portrait offers one clear advantage to the artist: while etching requires drawing the subject in reverse on the plate in order to print it facing the right way on the paper, for a self-portrait he can simply etch his face as he sees it in the mirror. This is very probably what Liotard did, as he wrote at the bottom of the plate: dapres nature [from life], to highlight that he etched his portrait directly on the plate with ground, without the help of a preparatory drawing (Hoisington, 2013, p. 95).

No impression of the first state of this etching is known. Until now, only one counterproof was known, in the collection of the Fondation Custodia (Collection Frits Lugt), and described in the Roethlisberger and Loche catalogue under no. 18: “Counterproof, almost certainly printed by the artist from a first, unknown, edition, perhaps for comparison with a presumed preparatory drawing.” (Roethlisberger and Loche, p. 244; ill. p. 243, fig. 24). While the existence of two counterproofs does attest that there was at least one impression of the first state, it is highly doubtful that Liotard copied a preparatory drawing: in that case he wouldn't have added the mention dapres nature. What is more probable is that, in the absence of a preparatory drawing, he printed the counterproofs in order to better see the detail of the drawing etched on the copperplate: this would have allowed him to more precisely place the new strokes that can be seen in the impressions of the second state, in the hair, on the face and in the background. Unless he wanted to print these counterproofs to represent his "self-portrait in the mirror"…

Impressions of this first etched self-portrait by Liotard are extremely rare. In his article about the acquisition of an impression of the second state by the Rijksmuseum (Bulletin 59 n°2, 2011), H. Leeflang lists only six, including the counterproof of the first state in the collection of the Fondation Custodia (2). The British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art (3), the Château de Versailles et de Trianon (Album Louis-Philippe) and the Rijksmuseum (4) each have an impression of the second state. The Bibliothèque nationale de France keeps an impression of the third state, printed in light brown and without the triangular mark on the edge.

To these impressions we can now add this second counterproof of the first state, with, on the back, the collection mark of Soliman Lieutaud (1795-1879), a painter and print dealer in Paris, known as “the man in France who has the best knowledge of engraved portraits” (Faucheux, Annuaire des artistes, 1860, p. 182, quoted by Lugt). Soliman Lieutaud published several reference books, among which lists of French engraved portraits. His portrait collection was sold at Drouot in February and May 1881; each sale lasted six days. The Catalogue des portraits français et étrangers de la collection de feu M. Soliman-Lieutaud iconophile (7 February 1881) listed 1375 lots. Number 805 mentions: “Liotard dess. et gr. par lui-même. Anonyme. 2 eaux-fortes. Rares.” [Liotard sketched and etched by himself. Without signature. 2 etchings. Rare.] This description corresponds to the annotation on the back of our impression, which could well be one of the two.

This self-portrait by Liotard was amongst the pieces collected in a quarto volume bound in the XVIIIth century, which contained around a hundred engraved portraits of painters, sculptors, musicians, physicians and scientists from the XVIth to the beginning of the XIXth century. The inside front cover of the volume had the ex-libris of Hippolyte Destailleur (1822-1893), an architect whose collection of French prints from the XVIIIth century was sold in 1890 (Lugt 740). In 2006, the exhibition Portraits d’artistes de la collection d’Hippolyte Destailleur at the Musée Carnavalet presented a series of drawings from his portrait albums. The Bibliothèque nationale de France keeps a collection of albums of drawings and engravings that was acquired during his lifetime (Fonds Destailleur).

(1) A counterproof is obtained by pressing a fresh print on a piece of paper, in order to reproduce the design facing in the same direction as on the plate.

(2) « sold by Christopher Mendez to the Lugt collection in 1982 » (British Museum, notice n°1852,0214.357). See also : Fondation Custodia, Morceaux choisis.... 1994, no. 75, p.162.

(3) « Christie's, Londres, April, 8, 2009 (lot 22); vendor: Helmut H. Rumbler » (Metropolitan Museum of Art, n°2009.229); Christopher Mendez, Londres (cat.50, 1982, no. 19, repr.).

(4) Bought in 2009: « The Rijksmuseum is especially grateful to Christopher Mendez for his indispensable help in acquiring the self-portrait of Jean-Etienne Liotard » (Leeflang, 2011, p. 207).

References: Drouot, 7-12 February 1881: Catalogue des portraits français et étrangers de la collection de feu M. Soliman-Lieutaud iconophile; Fonds du Château de Versailles et de Trianon, INV.GRAV.LP 67.94.1, Jean-Étienne Liotard; British Museum, 1852,0214.357: Self-portrait of Jean Étienne Liotard; Ed. Humbert, Alphonse Revilliod, Jan Willem Reinier Tilanus, La vie et les œuvres de Jean Étienne Liotard (1702-1789): étude biographique et iconographique, Amsterdam, 1897; Morceaux choisis parmi les acquisitions de la collection Frits Lugt réalisées sous le directorat de Carlos van Hasselt 1970-1994, Fondation Custodia, Paris, 1994; Hans Boeckh, Bodo Hofstetter, Renée Loche, Marcel Roethlisberger, Liotard: catalogue, sources et correspondance, Doornspijk, 2008; Christie’s, Old Master, Modern & Contemporary Prints, April, 8, 2009, lot 22: Liotard, Self-Portrait as a young Man; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.229: Liotard, Self Portrait as a Young Man ; Rijksmuseum, RP-P-2009-294: Zelfportret van Jean Étienne Liotard; Frits Lugt, Les Marques de Collections de Dessins & d’Estampes; H. Leeflang, 'Acquisitions: The Print Room: A Self-Portrait by Jean-Étienne Liotard from the Artist's Family Holdings', The Rijksmuseum Bulletin 59 no. 2 (2011), pp. 204-207; Rena M. Hoisington, in Perrin Stein, Charlotte Guichard, Rena M. Hoisington, Elizabeth M. Rudy, Artists and Amateurs: Etching in 18th-century France, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2013, pp. 95ff.